March is maple season in the Lake George Area

February brings frigid nights, where every exhale is a misty white, and warm days when the air is filled with the promise of spring. This combination of weather is ideal for sugar maple sap to run. The woods become alive with the chirps of birds and skitter of squirrels searching for a meal. Snowmelt turns the frozen ground into puddles of mud, and the sun hovers in the sky longer and longer each afternoon. When the weather breaks from brutal winter, commercial maple farms and local hobbyists start gearing up for maple season.

For many commercial farms, maple season means big business. They tap hundreds of sugar maple trees in mid-February in hopes of harvesting thousands of gallons of sap. Their vast, beautiful sugarhouses can produce hundreds of gallons of syrup and other products during those few crucial months.

For locals, NYS maple season is pure fun. It’s an excuse to walk their property and observe their sugar bush. They tap their own trees, hoping for just enough sap to cook up a gallon of syrup for their own table.

Then, there’s Up Yonda Farm Education Center, a dynamic outdoor haven in Bolton Landing. The mission of this 73-acre property is to celebrate the variety of natural gifts we have in the Adirondacks. The property is a playground of fields, forest, and outbuildings. Guests of Up Yonda can hike or snowshoe miles of trails, explore seasonal gardens and the butterfly house, meet turtles in the gift shop, and more.

One of Up Yonda’s specialties is teaching kids and their families about the magic of maple season. Their tour hits on the origin, history, science, and future of turning sugar maple sap into the sticky-sweet substance that most people love. The maple tour at Up Yonda Farm is one of the coolest Adirondack experiences in the Lake George Area.

Up Yonda Farm invited us to the facility on an overcast but warm late winter day in February. We met with Peter Olesheski, a staff member at Up Yonda who gives maple tours and works to collect the sap. Leading up to our visit, the weather had been decent for getting sap to run. Peter and the rest of the staff were excited.

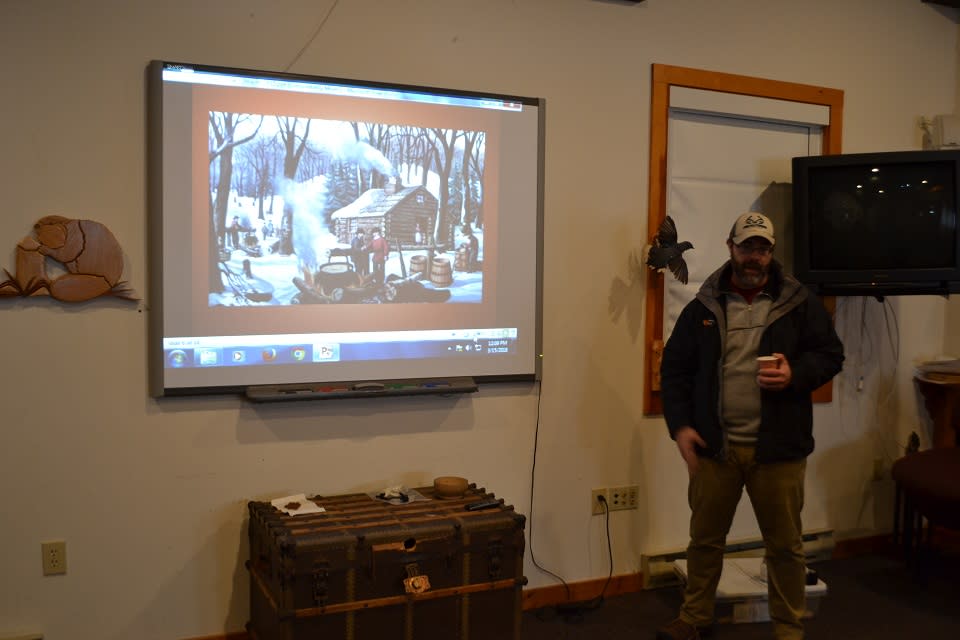

We started the tour in Up Yonda’s auditorium, a spacious square room with ancient wood tree taps, Native American arrowheads, and other artifacts on the walls. It’s kept dark so the projected presentation looks good on the southern wall. The presentation starts with a short slideshow covering the history of syrup. It begins with the maybe-accurate story of how sugar maple sap was first turned into maple syrup.

The magical and unlikely story of maple syrup began centuries ago, when Native Americans made an accidental discovery. This cooking mix-up created the wonderful tradition that thousands of people emulate every March.

The story begins in late winter, when Iroquois Chief Woksis realized his tribe was running low on food

He decided to lead his people on one more hunt to replenish their dwindling stores of food. In a frenzy of determined excitement, Chief Woksis swung his prized tomahawk into the thick trunk of a massive sugar maple tree. Leaving it lodged in the tree, he dashed off to form his hunting party.

After gathering his people, Chief Woksis ripped the tomahawk from the trunk of the sugar maple and dashed into the forest. Later that morning, the wife of Chief Woksis set out to do some cooking and cleaning. She needed water to begin her housework, but before she walked to the river she noticed a clear liquid flowing from the tomahawk wound in the sugar maple. She touched her fingers to the dripping liquid and sampled the sap. It tasted exactly like clean water.

Intrigued but occupied with her daily chores, she left a bucket under the flowing wound in the tree. When she returned hours later, the bucket was overflowing with sugar maple sap. She tasted the sap once more and detected a slight sweetness on her tongue. She decided to cook a stew for her husband using the maple sap.

The men returned from the hunt weary and hungry. Chief Woksis wasted no time and scooped himself a healthy serving of his wife’s stew. He immediately realized the stew was different and delicious. It was the most delectable food he had ever eaten. His wife told him about the wounded tree and the running liquid, and together they realized there was something special about sugar maple sap. The chief told everyone in the village to start slashing sugar maple trees, and from then on all of the tribe’s food was cooked in sugar maple sap.

The tribe collected gallons of the thin, clear liquid. Before long, they discovered more sweet secrets about the sap. They boiled sap in hollowed-out logs, transforming the liquid into a thick, dark brown substance. Continued boiling turned the sap into a rock-hard block, which the tribe could then scrape into their food as a sweetener. The magic and miracle of maple sap was born.

The process of cooking sugar maple sap into syrup has not changed since the days of Chief Woksis

However, gathering and cooking sap has become easier over the centuries thanks to the transformation of the tools and equipment used.

The Native American sap-gathering process was tedious. They used “mukocks,” or buckets made of birch bark to collect the liquid. Eventually, spigots made from hollowed-out branches were introduced, allowing spouts to stay in the trees. These revolutionary spigots made gathering sap easier and caused only minor damage to the sugar maples.

Native Americans introduced the maple process to Europeans, and equipment began to change more radically. Buckets, barrels, drills, hammers, horses, oxen, and cattle were introduced by Europeans, transforming the maple industry. These tools allowed for more efficient collection and boiling of sap. Since the maple sugar and syrup was heavily desired to sweeten food, it was all hands on deck with any tool that could help during maple season.

Modern technology is hugely important to Up Yonda Farm

There are only three full-time staff members at the facility, and they take advantage of all of the help and tools at their disposal. “We wouldn’t be able to even produce what we do if it wasn’t for the modern technology,” according to Peter. Their hard work and dedication amounts to a decent amount of syrup.

Up Yonda Farm uses gravity tubing to collect their sap. They only tap a few dozen trees for two reasons: they don’t have the manpower to tap tons of trees, and they are not a commercial maple farm. Up Yonda doesn’t sell their maple syrup, so they don’t need every drop of sap out of every single tree in their sugar bush.

The trees were tapped at Up Yonda. They had done that early work about two weeks before we visited. The sap was flowing but not yet running like the nearby Schroon River. The perfect temperatures for syrup are exactly like what you want for apples in the fall. “You want cool nights, and then it’s gotta warm up in the day. That changing temperature… forces the roots to pump out the sugar and water,” according to Peter.

After the presentation was finished, our next stop was the sugar bush. Set on a gently sloping hill, about 30 sugar maples stood tapped. Thin green and blue tubing ran tree to tree throughout the open woods. The wide blue lines are considered the main artery, running up the hill and lying within reach of every tapped tree. The green lines, smaller in diameter, are individual tubes that are connected to as many as three trees. The green lines collect sap from the trees and filter it into the blue line, which runs into a plastic holding tank at the bottom of the hill. Once the holding tank is full of sap, the four-wheeler it rests on is taken to the sugarhouse, where it’s stored in 100- and 150-gallon tanks outside.

Up Yonda does not need a complicated vacuum system because gravity does all of the work. Peter says, “Gravity is fantastic if you’re not going to use these fancier systems.” The small army of tapped sugar maples can produce about 50 gallons of pure Adirondack sap per day.

Though 50 gallons of sap per day won’t produce a ton of syrup over the course of the season, the small amount Up Yonda does produce serves a vital educational role. While learning exactly how Up Yonda turns sap into syrup, kids and families also learn just how unhealthy most typical, store-bought syrup is.

Many kids and families who take the maple tour have no idea how inauthentic generic maple syrup is. The rubbish from grocery stores is processed and refined. According to Peter, “most of this other syrup on the market contains zero maple sugar… It’s corn starch, sugar beets, and other stuff.”

Real maple syrup, like what’s produced at Up Yonda, is good for you. It’s made from pure maple sap alone. It lasts forever and is high in vitamins and minerals, such as zinc and magnesium, necessary for a healthy body. It’s barely regulated because there’s simply not many ways to corrupt it. Maple sugar may be the father of natural Adirondack products.

The sugarhouse represents an idyllic Adirondack enterprise

It’s a place of backwoods science, where generations of families that cherish the outdoors come together, celebrating the bounty of spring. To get to the sugarhouse at Up Yonda, guests walk a narrow, tree-lined road behind the main building. The road is snow-covered and the trees hang over the road, creating a natural dome.

About halfway down the road we stopped at a fast-running tapped sugar maple with a bucket hanging underneath the dripping spout. The bucket is made of thin metal. A lid on the bucket serves to keep dirt, branches, and animals out of the extract, though a hoof-kick from a deer could easily knock it off. It’s important to keep rain, snow, and gunk out of the bucket, because added water equates to longer boiling times to make syrup.

Scars in the trunk of the tree mark the spots where taps were placed in past springs. The half-healed markings signify a tree that is not completely healthy. Peter remarked that this tree is a great tool for teaching, because kids, "can visually see the sap running off the spout, they see it in the bucket.”

The bucket was nearly overflowing with clear sugar maple sap. We took turns sticking our fingers under the running liquid and tasting it. The sap tasted exactly like water to me, but some people can detect a faint sweetness. After taking a few more tastes of dripping sugar maple sap, we continued walking toward the sugarhouse.

Constructed in 2000, Up Yonda’s sugarhouse is a small, unheated log cabin structure. Boiling sap produces steam, so the top of the sugarhouse has a cupola, which opens to release the steam. “Our goal is to get rid of as much of the steam as quickly as we can,” Peter said. “If we don’t do that the whole building fills with steam and you can’t see what you’re doing.”

Half of the sugarhouse is standing room, where visitors to Up Yonda watch the syrup cooking process enveloped in steam and sweet smells in the air. Its walls are adorned with maple-themed posters, such as one showing where sugar maples grow in North America. The other half of the sugarhouse holds the boiler, which is the main tool for turning sugar maple sap into syrup. The syrup is cooked in a boiler run on kerosene, allowing for quick heating and easy temperature control.

The Up Yonda employee working the boiler adds sap into the top section of the evaporator pan. It’s then filtered to remove dirt and other muck. The sap must be heated to exactly 219 degrees and then removed to ensure its maple syrup-consistency. The team constantly checks the temperature with an antique candy thermometer to ensure the sap reaches but does not exceed the perfect temperature.

Once the sap reaches about 217 degrees, it’s drawn out and filtered once more. At this point, the sap is not syrup yet. It is dark brown and getting thicker, like frozen iced tea sloshing around in the pan. Once they have enough sap that is almost syrup, it goes into the bottler, where it gets heated up to the ultimate 219 degrees. They use a hydrometer, which measures liquid density measured in bricks, to make sure the syrup is at the right density and sweetness.

Finally, the syrup is bottled at 180 degrees. The team fills the bottle, applies the cap, and then flips the bottle upside down, coating the plastic in 180 degree syrup. This temperature guarantees that the syrup is safely sealed, killing any bacteria inside the plastic pint and half pint bottles. After bottling, the syrup is ready for pancakes and waffles on your breakfast table.

At the heart of Up Yonda Farm, they tell a chapter in the great Adirondack story that has been unfolding for centuries. They will never produce thousands of gallons of sugar maple sap. Their aim will never be to make money from their sugarhouse. Their aim is to educate and inform, whether it be through their maple tours or their other outdoor offerings, like moonlight snowshoe hikes, the butterfly garden, or the museum full of Adirondack animals.

So if you’re in the Lake George Area this spring, and you get that nagging craving for something sweet, check the schedule at Up Yonda Farm in Bolton Landing. You may leave with a half-pint bottle of pure Adirondack maple syrup, and a new hobby to boot.

Thanks to Matt Sprow for providing some of the photos in this article.