On a crystal clear night in late August, my girlfriend and I parked fifteen rows back from 150x50-foot screen two at the Glen Drive-In Theater. The sprawling field that serves as an outdoor movie theater was about a quarter occupied and filling quickly. Lifted trucks covered in mud, brand-new minivans full of kids, and couples sitting in compact cars like mine were scattered across faded grass throughout the field. Old, alien-grey metal speakers perched on four-foot high poles acted like ushers overlooking the crowd, making sure everyone had a comfortable seat and a clear view of the massive screen.

The evening was unseasonably cool, one of those nights that signal the end of summer and thoughts of notebooks and school clothes. Most of the evening’s attendees opted to sit in the warmth of their vehicles instead of braving the chill on the lawn. A few boys wearing jeans and sweatshirts lounged in the back of a pickup truck. A father and son stood in the gravel road tossing a baseball back and forth. A family of four took a few camp chairs out of their SUV and parked them under the glimmering stars, settling in for the movie with popcorn and candy in hand. A couple strolled in front of our red car with their golden retriever leading the pack. The Glen Drive-In, this hallmark of an America almost gone, is thriving.

The first film on the schedule was The Hitman's Bodyguard, an action-comedy starring Samuel L. Jackson, Selma Hayeck, and Ryan Reynolds. As the screen flared to life, we reclined in our seats and settled in for the previews.

Before the previews highlighted autumn’s potential blockbusters and burnouts, we were surprised to see a brief PSA on the screen. The announcement is theatrical, with a hefty helping of guilt thrown on top. It covered the history of the drive-ins, how significant these theaters were to American culture, and how thousands of drive-ins crisscrossed the country during their heyday. Sadly, the announcement confesses, only 400 theaters remain in business.

And then comes the plea. Drive-in theaters don’t make piles of money from ticket sales. That's why it's so important for movie-goers to hit the snack bar. Buy a juicy cheeseburger, a box of buttery popcorn, or a few chicken tenders for the kids. Without food sales at the snack bar, the remaining drive-in theaters around the country would probably disappear.

Brett Gardner, the proprietor of the Glen Drive-In Theater, is doing all he can to keep the last Lake George Area drive-in alive. A tall, lean man in his thirties, Gardner was born into a family of drive-in theater owners. His grandfather built theaters in the 1940s and 1950s. He would “buy the property and develop it, and figure out everything that was necessary to get a drive-in theater in there… and then build another,” said Gardner, whose grandfather opened the Glen Drive-In Theater in 1958.

The drive-in was a family business. Gardner’s father worked at the Glen Drive-In Theater and eventually came to own the property. He enjoyed working at the drive-in, so instead of building the business up to sell it like his father he decided to run the business, making his living from popcorn and ticket sales.

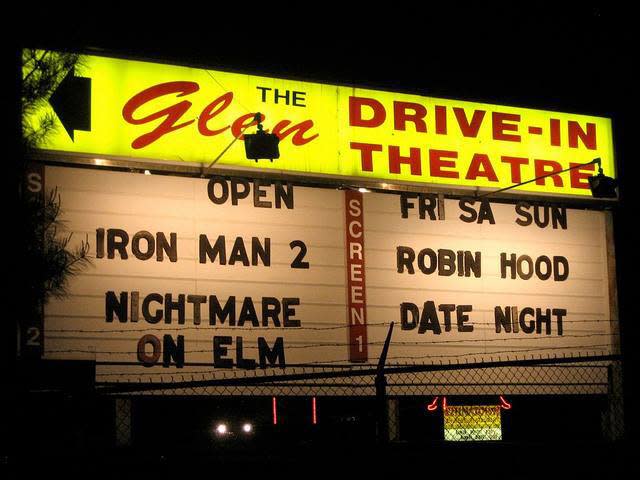

The Glen Drive-In was a central part of Gardner’s childhood. He grew up at the theater. His parents worked there full time, so the school bus dropped him off underneath the yellow “Glen Drive-In Theater” sign instead of at their family home. So in 2002, when Gardner’s father was considering retirement from the drive-in theater business, he gave his son a choice. His father wanted to keep the theater in his family, but only on one condition: Gardner had to prove that he was up for the challenge. His dad told him, “I want to see you fix things, I want to see you work on things, and I want to see you at the theater at least 40 hours a week.”

Gardner got to work. He quickly rediscovered what he already knew. Running the Glen Drive-In Theater wasn’t a normal nine-to-five gig. The management, maintenance, and general tinkering completely encapsulated his life.

A summer workweek at the drive-in approaches 60 hours. Gardner’s typical week consists of grounds maintenance, staff management during show times, and the bane of his existence, paperwork. Before families see the manicured lawns underneath the lit up screens, Gardner has spent close to 18 hours a week mowing and, “weeding all the poles, weeding all of the fence lines, and blowing off all the roads.” When the drive-in is open, Gardner spends hours “doing the inventory, dealing with the scheduling, being here to run the theater, and then leaving at 2 o’clock in the morning.”

The work isn’t over after the final car drives away from the lot each fall. Every off-season brings a big project, like overseeing the construction of a new garage or renovating the upstairs projection room. Gardner takes care of most of the maintenance, such as “little plumbing issues, minor upgrades on electrical,” and other jobs that he can handle himself. Some work gets hired out, but Gardner tries to do the majority of the work on his own. Thanks to his father and grandfather before him, revamping the theater is in his blood.

He’s proud to be so hands-on. Gardner doesn’t see his business as a cash cow. Other than in the winter, when “the property is a frozen tundra,” Gardener is working, maintaining, and improving the business. When he’s not busy mowing lawns, doing maintenance, or finishing paperwork, he’s serving popcorn, frying chicken fingers, and flipping burgers on the grill.

Gardner has to do the work if the Glen Drive-In is going to survive. The movie industry doesn’t make it easy on independent owners striving to be self-reliant. Gardener was forced to buy and install brand-new digital projector equipment in 2013, which put a clearer picture on the drive-in’s screen and enhanced protections against piracy. The old equipment was in perfect condition. “It was scary for the entire industry,” Gardner said with a shake of his head. The upgrades came to about $180,000, but Gardner had no choice in the matter. Hollywood had decided, “we’re not going to give you 35mm content anymore. You have to get the digital projectors.”

Not only was the modern equipment expensive, it’s more difficult to maintain than the 35mm projector. When the new equipment fails it’s difficult to find someone to repair it. Gardner and his father were experts at fixing their old projector, having spent hours learning the ins-and-outs of the equipment. After the digital change, “you can’t do any of that. Everything is digital. Every single thing. So if you get one piece of software that fails, one disconnected something in that network, a security failure. No one can fix it.”

Drive-in theaters haven’t changed much since their peak in the 1950s. They’re still a place where families can pile into the car and spend a few hours in the company of one another. What has changed is the way that families consume content. Some may see the drive-ins as outdated, opting instead to sit in the comfort of their family room and stream a movie. Instead of worrying about this growing trend, Gardner trusts Hollywood to put out solid content. “I have to rely on the studios to put out what they think is going to make them money so that I can piggyback off of them. As long as they put out the content that people want to see, that’s going to bring people out to the drive-in theater.”

Even though Hollywood consistently pumps out blockbusters, Gardner still has to determine which films will bring customers to his drive-in. Choosing successful movies is a mix of science and art. Gardener has a booker who suggests films to bring in based on tracking. And although he tries to trust his booker’s instincts, Gardner often finds a title that he wants at his theater for one reason or another. He puts his foot down about once a summer, like he did for the Alien franchise’s most recent offering. “If the one that I want is second best or second tier, I’ll try and fight for that. This is the one film I want this season. Alien: Covenant was one of those.”

He knows from decades of family experience that certain genres perform better than others at the drive-in. Niche films, like fall 2017’s blockbuster It, based on the novel by Stephen King, is never going to be popular at the drive-in. When it comes to movies like It, “families aren’t coming. Half of the girlfriends aren’t going to watch it, and a lot of people just don’t care about horror movies.” On the other hand, children’s movies and family movies perform well because the drive-in is a family place.

When you arrive at the Glen Drive-In Theater before the screens flash to life, in the middle of the summer when it doesn’t get dark until 8:30, it’s clear that going to the drive-in is an event perfect for families. The mowed and matted down lawns and dusty, gravel driveways of the Glen Drive-In are crawling with kids.

They fling Frisbees back and forth in between gulps of soda and handfuls of popcorn. A troop of giddy middle-schoolers belt “happy birthday” to a lucky kid before hands reach over to grab frosted cupcakes from a card table. The drive-in is where families go to get the together time that seems to be eroding in the modern age. “If you get here nice and early, you can hang out with your family, walk your dog, play some Frisbee with your kids, and get some snacks. You’re stuck here,” says Gardner.

The old-school family nature of the drive-in isn’t the only factor that stirs the overwhelming feeling of nostalgia when you roll into the parking lot. Close to one thousand gray speakers stand on the lawn of the Glen Drive-In, only some of which work. Gardener struggles to keep them all operational. His father always wanted to keep them working, so his parents spent about four hours a week repairing their inner workings despite the cost and time commitment.

The speakers break easily. People hang them on their partially-opened windows and accidentally rip at the cords, or let them fall from the top of the poles, damaging them in the process. Gardner chose to stop fixing them, assuming most people bring battery operated radios or listen in the comfort of their car.

Gardner was surprised when some of his customers began to complain that some speakers weren’t functioning. In an attempt to please people pining for the old days, he hatched a plan to fix the speakers located in the middle of the theater. “I’m going to have the whole center operational, so if you want to use a speaker you’ve gotta get here early.” People get their speakers, and that patented drive-in look stays intact. Everyone is happy.